Presenting Author:

Michael Bancks, Ph.D.

Principal Investigator:

Mercedes Carnethon, Ph.D.

Department:

Preventive Medicine

Keywords:

racial disparities, incidence, type 2 diabetes mellitus, epidemiology, observational study, young adulthood

Location:

Third Floor, Feinberg Pavilion, Northwestern Memorial Hospital

PH42 - Public Health & Social Sciences Women's Health Research

Factors associated with the observed racial disparity in diabetes incidence

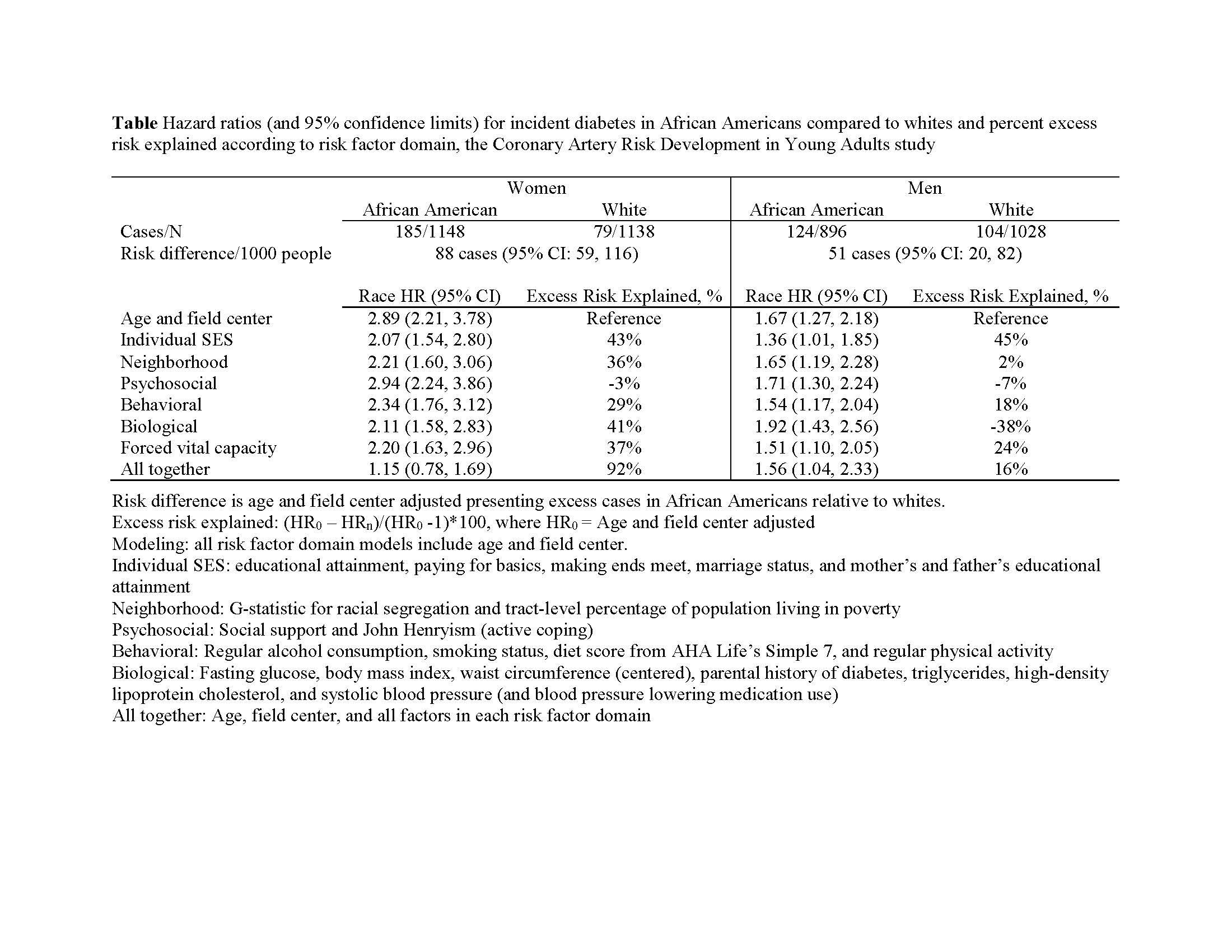

Importance: In epidemiologic research, disparities in the incidence of diabetes are observed when comparing African Americans to whites. The extent that modifiable factors contribute to these observed racial disparities and whether they differ by sex remains unclear. Objective: To quantify the percentage excess risk that modifiable socioeconomic, neighborhood, psychosocial, behavioral, and biological factors contribute to the observed racial disparity in incidence of diabetes between African Americans and whites. Design, Setting, and Participants: We used data from the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study of black and white young adults enrolled in 1985-1986. Standardized questionnaires were used to assess baseline socioeconomic, neighborhood, psychosocial, and behavioral factors and valid clinic protocols were used to measure baseline biological factors and determine diabetes status at 8 in-person follow-up examinations. Sex-stratified multivariable adjusted Cox proportional hazards modeling was used to estimate hazards for incident diabetes over 30 years and percent excess diabetes risk, comparing African Americans to whites. Exposures: Self-identified race: African American or white. Main Outcomes and Measures: Incident type-2 diabetes mellitus. Results: Among 4210 participants included for analysis, 49% were African American, 54% were women, and the mean age at baseline was 25 (SD, 3.6) years. We identified 492 cases of incident diabetes over a median follow-up of 29.7 years. Compared to an age and field-center adjusted model, we observed the largest percentage of excess risk explained for men (45%) and women (43%) after adjustment for individual-level SES factors (see Table). After adjustment, African American men had 1.5-fold greater risk for diabetes than white men, whereas a disparity was not observed for women. For both sexes, BMI and paternal education explained considerable excess diabetes risk in African Americans, while other singular factors differed in strength and magnitude by sex. Conclusion and Relevance: We observed African American men, but not women, remained at increased risk for incident diabetes compared to their white counterparts after adjustment for modifiable socioeconomic, neighborhood, psychosocial, behavioral, and biological factors. These results suggest common factors contribute to observed racial disparity in diabetes, but also that factors may differentially explain the observed racial disparity in incident diabetes according to sex.